Operation Paperclip

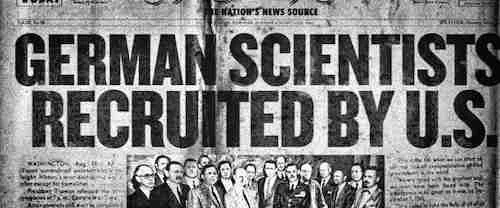

When the existence of Operation Paperclip was first revealed to the American public in 1946, the general consensus in the country was that it was a bad idea. Prominent figures, including former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, were vociferous in their disapproval. The United States had, after all, just fought a world war against the Nazis. They were the bad guys.

For the architects of Operation Paperclip, it wasn’t so cut-and-dried. In the larger terms of US national defense, the criteria for who could be classified as “the enemy” was quickly changing. Even before the fall of Berlin, American intelligence agents had begun quietly tracking down and recruiting Nazi scientists and engineers with expertise in electronics, medicine, aerospace, rocketry, chemistry, and other wartime technologies — expertise that could give the Western powers a greater edge in the burgeoning Cold War. In all, more than 1,600 Nazis were given safe haven in the United States so their skills and knowledge could be exploited to maintain American military superiority.

After The New York Times and Newsweek broke the news about Paperclip in 1946, government officials assured the American public that the individuals recruited in the operation were the “good Nazis,” insisting that none of them had been complicit in the atrocities committed by Hitler’s regime. In reality, however, there were a number of known war criminals among them, including some who had conducted human experiments, used slave labor, and even overseen the systematic murder of thousands.

It was Moscow’s own version of Operation Paperclip that had sent the US scrambling to enlist as many Nazi scientists and engineers as it could. Washington was willing to overlook their egregious crimes because the battle lines were shifting. With the defeat of Hitler, America’s World War II ally, the Soviet Union, had instantly replaced the Third Reich as its primary enemy, and the two sides were now locked in a technological arms race that would ultimately bring the world to the brink of nuclear annihilation.

From Operation Paperclip: The Nazis Recruited To Win the Cold War

by Randall Stevens, June 28, 2023

Timeline

Resources

-

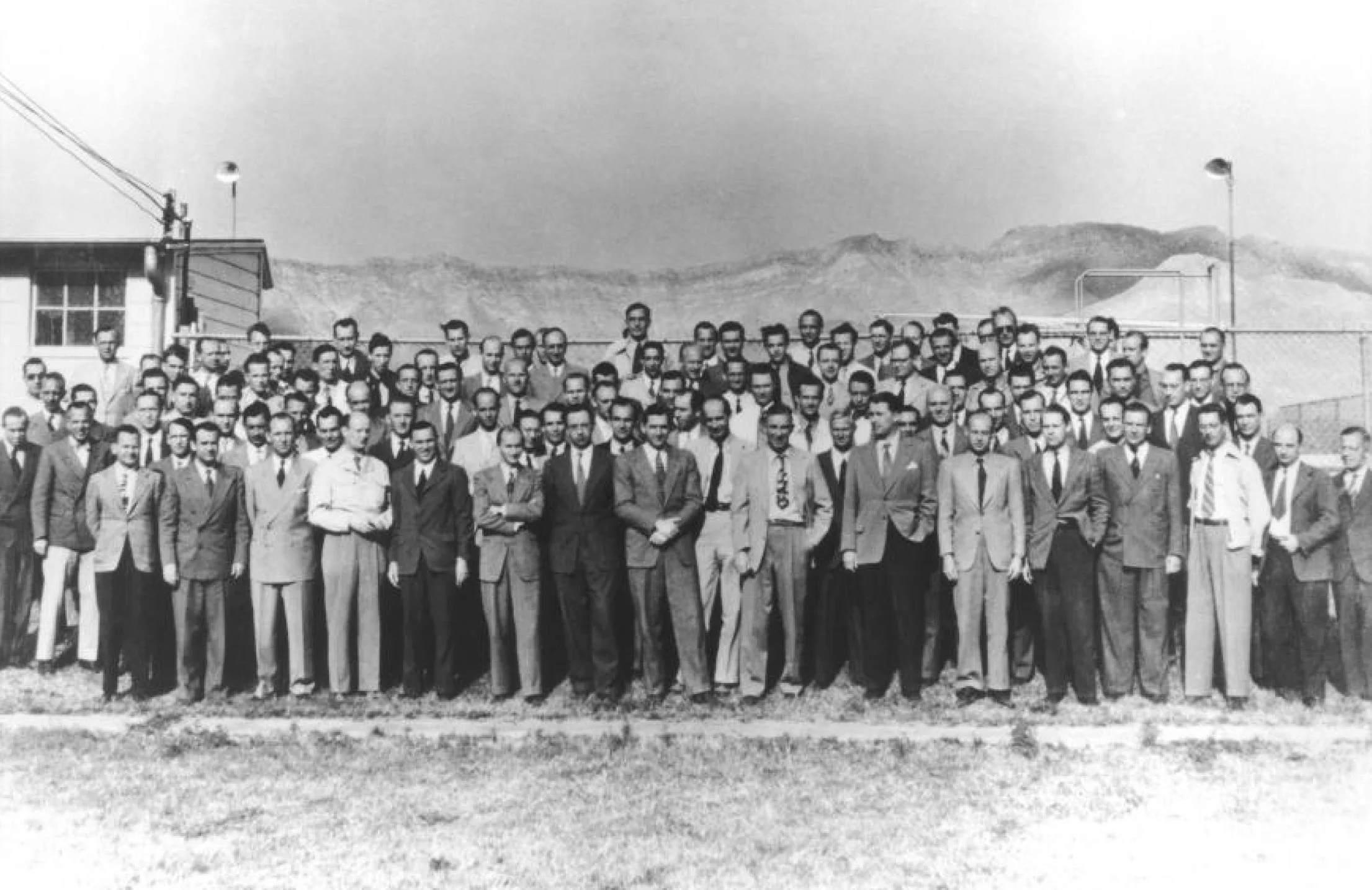

Operation Paperclip at Fort Bliss: 1945-1950

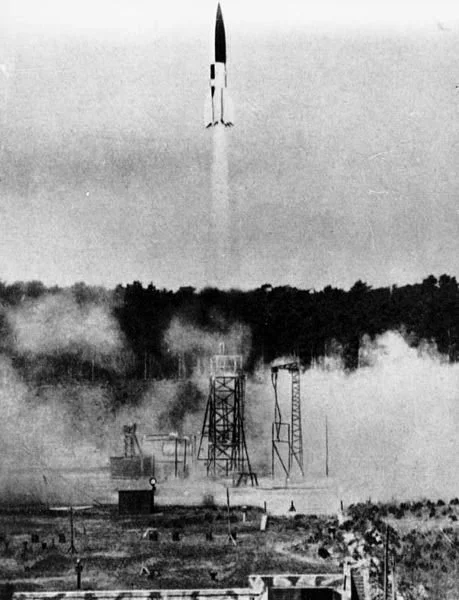

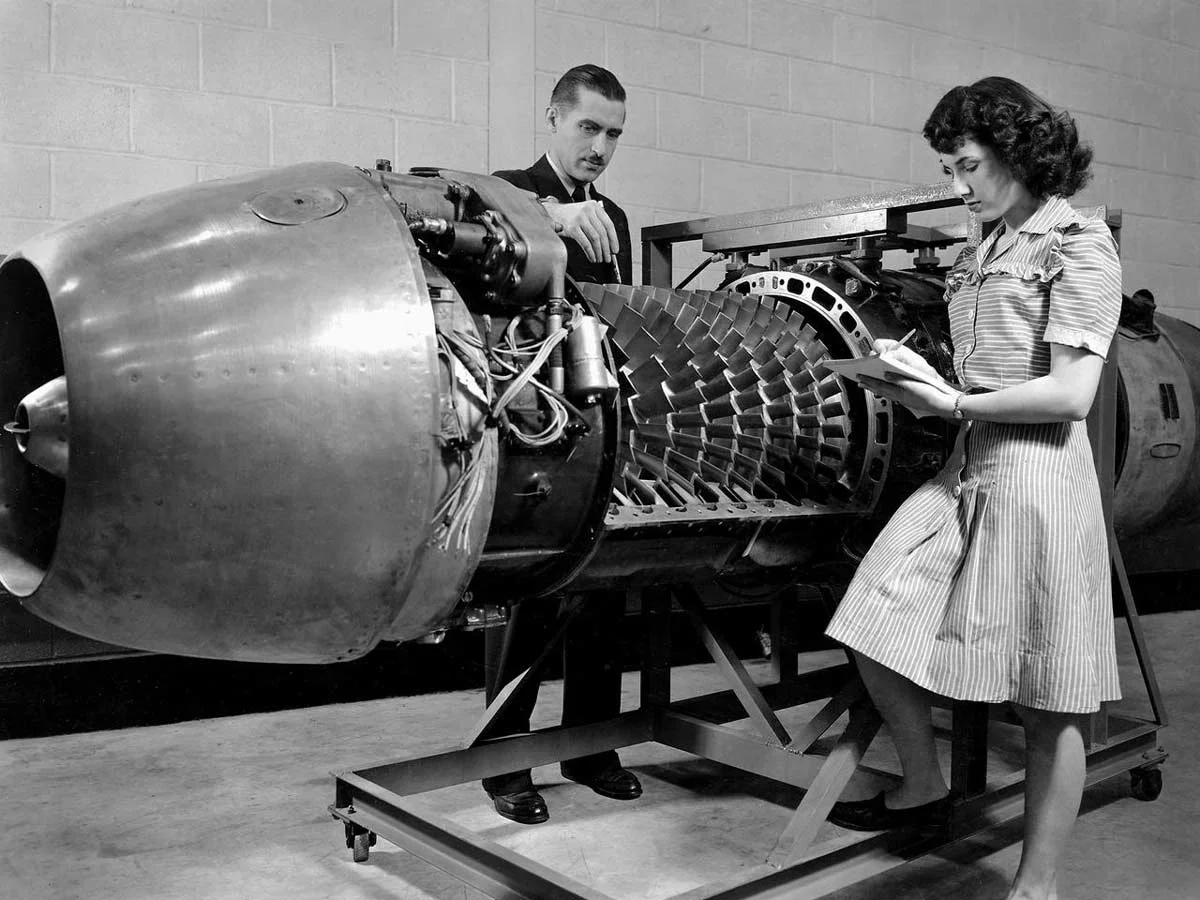

Germany’s use of its V-1 jet-powered flying bombs and V-2 rockets during the latter stages of World War II ushered in the era of guided missiles. After the war, as tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union increased, both countries sought to develop their own arsenal of guided missiles. In the ensuing arms race, both moved to first exploit and then improve upon Germany’s advanced rocket technology. Lieutenant Colonel Harold R. Turner, first Commander of White Sands Proving Ground, plainly stated the rationale behind this effort. “We must support and actively engage in a program of research and development that will provide us with weapons of greater power and greater range than any other nation can produce, and maintain for years to come a superiority in this field which is unquestionable and which is known to our potential enemies.” In the years right after World War II, the U.S. Army capitalized on the German progress to research and develop their own series of rockets and long-range missiles. The U.S. Army post of Fort Bliss, Texas had an important role in this exciting early American rocketry period.

-

Operation Paperclip: how the US recruited Nazis after WW2

We are led to believe that at the end of the Second World War in 1945, all of the Nazis were either killed in battle or captured by the heroic Allies.

We are led to believe that in the years following the war, the surviving Nazis were all tried for their crimes during the war against mankind.

We are led to believe that, aside from a few that found safe refuge in far corners of the globe, in places such as Bolivia, Argentina, New Zealand and some less-habitable locations, justice for all Nazis was swift and served as the great equaliser.

What we are not told as part of this narrative is where a group of over 1,500 Nazis disappeared to at the end of the Second World War.

-

Operation Paperclip

More than 1,500 German scientists, engineers and technicians (many of whom were formerly registered members of the Nazi Party, some were party leaders) were recruited and brought to the United States. After World War II they were hired under Operation Paperclip by the U.S. government to gain scientific and military advantage during the Cold War and, later, Space Race. (Paperclips were attached to the scientists’ new work as U.S. Government Scientists, thus the name.)

-

Operation Paperclip Casefile

Operation Paperclip was the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) program used to recruit the scientists of Nazi Germany for employment by the United States in the aftermath of World War II.

-

Operation Paperclip: How A Nazi Scientist Helped America Reach The Moon

On the morning of July 16, 1969, Neil Armstrong and the crew of Apollo 11 left Earth’s atmosphere on their way to the moon.

The day was tense. The moon landing was (and remains) possibly the greatest feat of engineering in human history, but success was by no means a guarantee. In the Command Room at Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, NASA’s best and brightest were a ball of nerves, mainlining coffee and chewing their fingernails.

All except for Wernher von Braun.

-

Families of Operation Paperclip

In 1945 during the cold war and the space race with Russia, the United States conducted Operation Paperclip. Over 1600 German scientists, engineers, and technicians were taken from Germany to work for the U.S. government. Operation Paperclip’s purpose was to aid and advance the U.S. military during the cold war. This isn’t a video about the scientists and engineers, but about the 108 families stationed at Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas. Thank you for watching From the Space Vault!

-

The Horrible Secrets of Operation Paperclip: An Interview with Annie Jacobsen About Her Stunning Account

The journalist Annie Jacobsen recently published Operation Paperclip: The Secret Intelligence Program that Brought Nazi Scientists to America (Little Brown, 2014). Scouring the archives and unearthing previously undisclosed records as well as drawing on earlier work, Jacobsen recounts in chilling detail a very peculiar effort on the part of the U.S. military to utlize the very scientists who had been essential to Hitler’s war effort.

-

Indiana Jones And The Project Paperclip Nazis – OpEd

The new Indiana Jones movie, Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny, shares much in common with the first movie in the series — Raiders of the Lost Ark. Among the common features is that the villain in the new movie, as in Raiders, is a German Nazi.

Image © 2022 Lucasfilm Ltd.

-

From the Mixed-Up Files of Dr. Wernher Von Braun

“ROCKET SCIENTIST” – A central element to the Space Camp history pedagogy is the distinction between a “Missile” and a “Rocket”. Beyond the technical difference in payload—a missile carries munitions, a rocket carries a capsule—the students are encouraged to think about the difference in purpose: a missile explodes, whereas a rocket explores. Setting aside the assumption that exploration and destruction are so easily bifurcated (and we are talking to nine-year olds; a lot of assumptions will be ignored), note how even this seemingly simple characterization of von Braun as a “Rocket Scientist” is an apology. Not only does this, given the Space Camp’s definition of a rocket, deftly dismiss his role in the military, more generally it points our attention to his genius (which is undeniable) rather than the ethics of what that intellect was put to.

-

Operation Paperclip: What the US Did With Nazi Scientists After WWII

Operation Paperclip (formerly known as Operation Overcast) was initiated in 1945 by the newly established Joint Intelligence Objectives Agency (JIOA) of the United States. As tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States over global domination grew, the Truman administration envisioned Germany’s scientific and technological advances during World War II as a valuable potential asset, particularly for military and rocketry development.